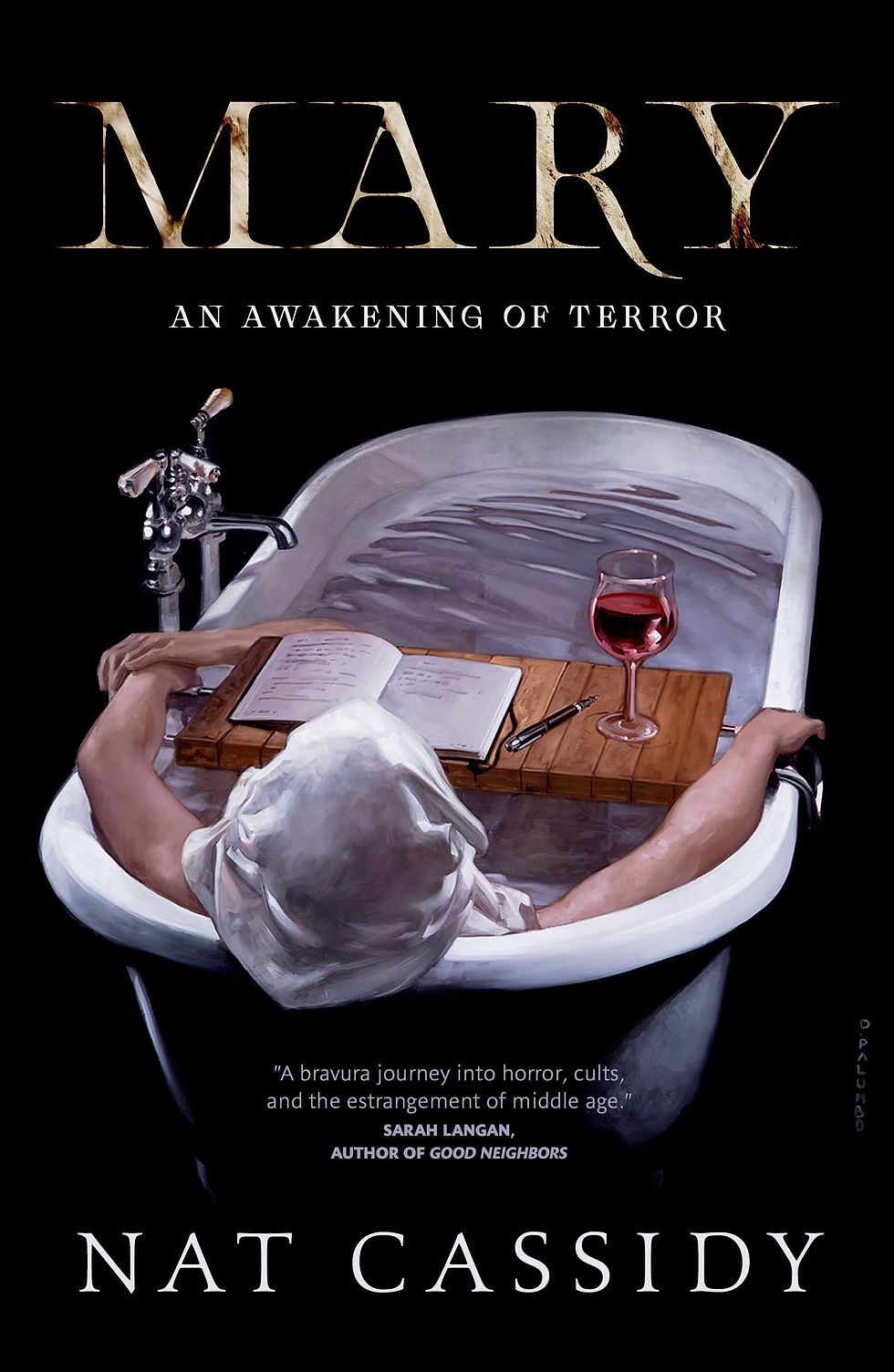

‘Mary: An Awakening of Terror’ Review & Analysis

- zachlaengert

- Sep 16, 2025

- 6 min read

Internalized phobias // who can tell what stories

Intro & Summary

Apparently two monthly book clubs weren't enough for me, because I decided to join a third – giving myself less than two weeks to read the 405-page Mary: An Awakening of Terror in addition to my standing reading obligations.

And I'm glad I did! Nat Cassidy's novel is a compelling one, with a satisfying level of horror aiding the exploration of an often overlooked and rarely discussed topic: society's dismissive view of aging women.

Spoilers ahead. I won't go into it here, but I'll warn that this book does contain some violence against animals, in case you're thinking of picking it up yourself.

Mary: An Awakening of Terror follows – you guessed it – a woman named Mary, who is approaching the age of fifty without having lived very much life. If not for the violent and disturbing prologue which straightforwardly establishes that she's secretly quite messed up, born at the same instant a serial killer was struck down and later seen eating pinned bugs from a museum as a young child, Mary would appear entirely innocent and unimposing at the start of the novel. She spends her days cataloguing the tomb-like basement of a bookshop, and her only hobby seems to be collecting and talking to small porcelain figurines she refers to as her 'Loved Ones'.

But Mary has a problem. She can't look at the faces of women her own age without seeing them rapidly age and rot before her eyes. She can't even look in the mirror for more than a few moments without fainting. Of course she goes to the doctor (or at least a free clinic, American healthcare being what it is), but he's happy to write it all off as side effects of her perimenopause, with perhaps a little hysteria for good measure.

Soon after, Mary gets fired from her job – her boss having meant to do so weeks ago but having forgotten about her – and hears from her horrible Aunt Nadine who needs someone to help her out around the house back in her hometown of Arroyo. Nadine is predictably abusive, the town is predictably creepy, and over time Mary learns the story that many readers will have put together from the prologue.

Fifty years ago, a serial killer named Damon Cross went around gaining the trust of lonely middle-aged women before murdering them and removing their faces. (Towards the end of the book, we learn that his own abusive father had locked him in a bathroom with the decomposing corpse of his mother for three days as a young child. Funny how that works.) Mary realizes that she's possessed by Damon, that he is seen as a prophet by the town, and that the head-covered ghosts she sees around the town are his victims.

Ultimately, it's revealed that her condition is simply because Damon can't stand to look at the faces of middle-aged women (let alone Mary's own face) and that by accepting herself for who she is – and letting the ghosts rip and tear Damon – Mary can finally overcome her problems. The ghosts – named after the Furies towards the end – also massacre the town cult, which ends up getting blamed on the most innocent woman in the world (also around her fifties) because it was convenient to the authorities. Meanwhile Mary vows to travel with her Erinyes entourage and exact some more violent revenge – seemingly against her former boss for firing her – but is conscious of the fact they will turn on her in time.

The Good and the Superfluous

The more horror and thriller stories I engage with, the more I appreciate the rare few which truly allow their characters to act with reason and intelligence as they come into contact with inexplicable forces. Mary: An Awakening of Terror mostly works for me on this front. Mary is actively looking for solutions to her problem from beginning to end, and ultimately only fails to find them in most cases because the people she turns to are secretly members of the cult. It's a little frustrating that she never even considers turning to Nadine – a conspiracy theorist and amateur paranormal investigator – for help, but also entirely understandable given their relationship.

On the other hand, it gets harder and harder to sympathize with Mary each time she refuses to acknowledge the strange moments she finds herself in before and after Damon takes over. (Granted Carole and partially Wallace are red herrings, but there are still 4-5 moments any sane person would be questioning more than Mary does.) A little mindfulness would go a long way with this woman, but alas.

I personally could have done without the cult plotline, which at the best of times felt tonally out of place and at the worst was just hollow conflict in Mary’s way. I can see why Cassidy chose to employ it: isolating and gaslighting Mary, adding a mysterious and claustrophobic atmosphere, connecting past and present. But between Damon’s rambling being taken as scripture, the odd shoehorning in of the desert and the random eye tattoos it really feels like bloat, which no one needs in a book over four hundred pages long. Perhaps leaning more into Mary and Damon’s internal lives could have been more rewarding, whether or not you then (much later) reveal that a cult has been influencing Mary’s experiences.

On the subject of past mirroring present, I really liked the epigraphs seemingly pointing at Damon’s initial killing spree but ultimately being revealed to be about current events.

Internalizing Societal Fears

The greatest strength of this novel has to be the way Cassidy explores Mary’s internalized fear, disgust and hatred toward people like herself. As with many speculative fiction stories, this real phenomenon is made literal here, by having Mary see herself and others through Damon’s traumatized, demoniac eyes. (Though I'm not entirely sure why it only became a problem when Mary herself reached that age. Maybe until that point she had also been simply ignoring older women around her?)

I don't think it's a stretch to say that a lot of the evil in our world stems from internalized self-hatred very much like what Mary is experiencing. Trump would never have won a first term, let alone a second, if he hadn't been preying on followers' internalized classism, racism, homophobia, misogyny and more. How much bullying and violence is simply the result of seeing someone else be comfortable owning something that you've been taught to repress?

Who can write what stories?

Here's the twist, if you haven't guessed it yet: Nat Cassidy, author of Mary: An Awakening of Terror, is a cisgender man. He goes into the issue in the book's appropriately titled "Afterword—or—What's This Asshole Doing Writing a Book About Menopause?" – which I highly recommend reading if you're interested. (I'll hyperlink it here, but who knows how long until this file gets taken down.)

His gist is that he's not 100% sure he's allowed to tell this story, but that he feels it is an important story to tell and that: "All I can really do is present this story as effectively as I’m capable of, honoring the material with all the humility, curiosity, honesty, and due diligence possible." His goal in the afterword is not to shut down criticism but to start a conversation.

And I think, as Haley Newlin at Cemetery Dance seems to agree, this is the best possible approach to the situation. Things get problematic when authors flagrantly steal stories, claim they have the authority to speak for groups of people they don't belong to, and when they refuse to engage curiously and respectfully with the subject they want to write about. It's plain to me that Cassidy fits into none of those categories, but kudos to the guy for still welcoming conversation on the topic!

Conclusion

While Mary may have offered me a little frustration here and there, I'm very glad to have read this book on a topic that's almost never been mentioned, let alone focused on, in anything I've read previously. I also come away with a great deal of respect for Nat Cassidy, who has clearly put a lot of care and thought into a potential issue that many authors would rather to simply ignore than to engage with at all – much like how a certain fictional town dealt with women of a certain age.

Mary reminds me in some ways of Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin, which explores post-apocalyptic transphobia with similar attention to internalized fears. Felker-Martin has had a week, so consider buying or borrowing her book(s) if you're so inclined!

Let me know if you'd be interested in reading more reviews like this, where I give more summary of the text in addition to exploring its themes & meaning for us as individuals and a society.

Thanks for reading and until next time <3

Comments