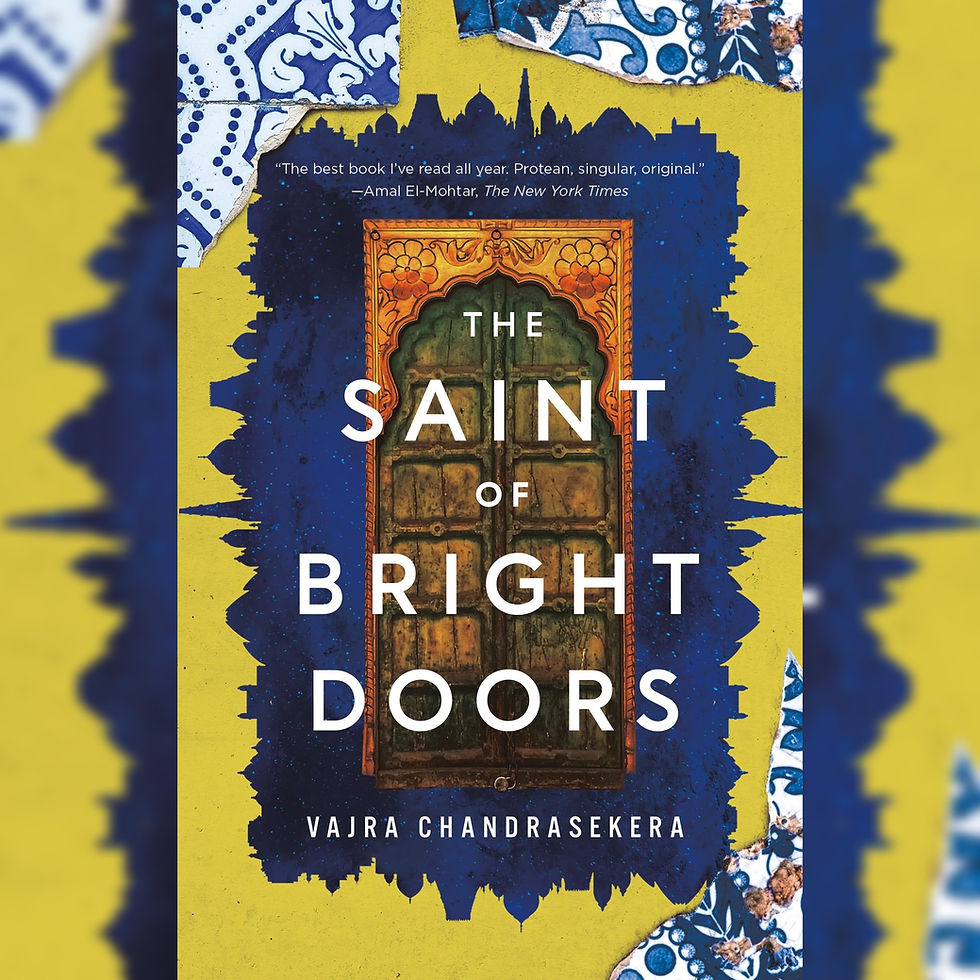

The Saint of Bright Doors: Lost in the System

- zachlaengert

- Mar 2, 2025

- 5 min read

How form & content unite in two chapters from Vajra Chandrasekera's self-reflective novel

Mimesis

I've always been fascinated by moments in books and other media where the way the story is being told mirrors or emphasizes its content or message. It's hard to find a perfect term for this idea in books and film; mimesis is the best the internet could offer me.

Video games actually have their own term: ludonarrative describes the relationship between a game's story as it is told to the player and the story the player experiences through actual gameplay. If two 'Game of Thrones'-licensed video games use the same cutscenes and dialogue but one uses slot machine mechanics and another is a political real-time strategy game, one will clearly have stronger ludonarrative than the other.

Video games must constantly think about the relationship between form and content, meaning dissonance between the two will be remarked upon far more often than harmony. The same isn't particularly true for other media, where giving attention to this relationship is rare. Purposefully creating dissonance would probably just come off as bad writing/editing/directing; imagine a deeply heartfelt moment in a film edited with the velocity of an action scene – it's nonsense.

Therefore when I write about mimesis you can assume I'm talking about positive relationships between form and content, where they support and strengthen each other. House of Leaves' warped text layout is a strong example of this, sharing the characters' discomfort and difficulty traversing the House with the reader as they work through the book. Another classic example is Moby Dick, where narrative progress is routinely paused for long (non-fiction) chapters about whale anatomy, whale painting, whale hunting, etc. in order to mirror the feeling of a long sea voyage.

The Saint of Bright Doors

The Saint of Bright Doors is a fascinating novel following the life of Fetter, who was fathered by the godlike cult leader Perfect and Kind, mothered and raised by Mother-of-Glory and expected to kill them both:

The Five Unforgivables are, in order of severity, matricide; heresy leading to factionalism; the sancticide of votaries who have reached the fourth level of awakening; patricide; and the assassination of the Perfect and Kind. By definition, they cannot be forgiven and cannot be redeemed. That means that if you commit any one of them, the cult will hunt you for the rest of your life, and make your name a curse for generations to come. Your mission is to commit them all. Your father abandoned us. We were unchosen, cast out of his eschatology. We are going to destroy your father’s cult and salt the earth where it falls. - Vajra Chandrasekera, The Saint of Bright Doors

Adult Fetter ultimately finds himself in the city of Luriat and attending a support group for fellow 'unchosen': chosen ones of various religions and traditions who were either cast out or escaped before fulfilling their calling.

It's a wonderful concept, and Chandrasekera doesn't shy away from exploring the various traumas the unchosen have experienced. Fetter, torn of his shadow and trained over years for a single violent purpose, finds he is truly unremarkable in the context of this group and takes comfort in the solidarity their meetings provide.

But back to mimesis. This whole novel reminds me a little of Samanta Schweblin's Fever Dream, where the writing and pacing evoke an unreal, nightmarish experience for the reader mirroring the character's experience. The Saint of Bright Doors places the reader very much in Fetter's perspective and closely mirrors his experiences. When Fetter is sick or despondent and unaware of the world around him, so are we. When he is alert and interested, we get details of and reflection on events.

There’s actually a great reason for this too; but I won’t spoil the ending today. Instead, let’s follow Fetter to prison. At one point the story finds Fetter attempting to return to Luriat after visiting home. He is at one of his lowest points, and so pays little heed to the fact that the city is on high alert for travelers due to an ongoing plague.

He’s stopped at the train station, can’t provide his papers and barely responds to questioning. And just like that, he is consigned to the system. Still highly despondent, he vaguely believes that it will all be sorted out while reacting very little. His first two jails pass by quickly - though not without their own eerie moments - before he finds himself being led through the gate of a large prison camp.

The Prison

Fetter is assigned a district while entering, but he "clutches at and immediately loses" its number, so decides to simply pick a direction and start walking:

The prison camp is at least as enormous as Fetter assumed it could not possibly be. He has no idea how deep it goes. He seems to have entered an entire town with its own neighbourhoods and a grid of roads that grows more haphazard the further he walks.

He travels for weeks, working for food and shelter where he can and confident that the outer fence of the prison will surely be just a little further. It isn't. This prison camp is far larger than the city itself, made up of thousands of neighbourhoods with their own makeshift governments and economies. Guard stations become less and less common the further Fetter walks; mail and summons to court are unheard of in distant districts. Eventually long stretches of emptiness divide the districts, only connected by dirt trails.

My favourite scene of the novel sees Fetter reach a tiny district in a marshy land. He encounters a familiar face from the city, who earnestly believes he and his sister are simply traveling home and has no concept of the prison that supposedly surrounds them. Is it possible the walls went up around him, or has he forgotten his incarceration? The book doesn't answer, because just as Fetter begins to wake up to this bizarre world a guard arrives on a motorcycle with a summons for him.

It turns out this was his assigned district.

While hardly essential to the book’s plot, these two chapters stood out for how powerfully they capture the feeling of being washed away and lost in an alien environment, at the mercy of forces beyond your control.

The system forces Fetter to simply survive, giving him no time or capacity to question the dream-like illogic of his situation. For a time he joins the rest of the prison population in apparent non-existence, utterly lost in a system that otherwise places great care in categorizing its citizens.

By uniting the framing of Fetter's perspective with a surreal setting and elusive plot, Chandrasekera achieves a mimesis that captures a real feeling of powerlessness and disorientation. Many people will seemingly live and die within this endless, apathetic prison and might even forget their circumstances – just as they do in the oppressive systems of our own world.

Set Free

Of course (un)chosen Fetter is the exception to the rule, however much he might crave to truly disappear. His release is only secured because his father, the Perfect and Kind, has summoned him. This is another small point of mimesis, the plot employing an unavoidable call to adventure to reign in its reluctant protagonist.

There's much more to reflect on in this book. The perspective mirroring Fetter's mood is similar to how the world around him is revealed to have been shaped by his father's whims. Fetter and the other unchosen are all reflections of the groups that produced them; their hopes, fears and dreams.

The Saint of Bright Doors has a lot to say about identity, existence and so much more. Consider giving it a read!

Thanks for joining me for this little fever dream, until next time <3

Comments